Lal Singh’s red flag for journalists

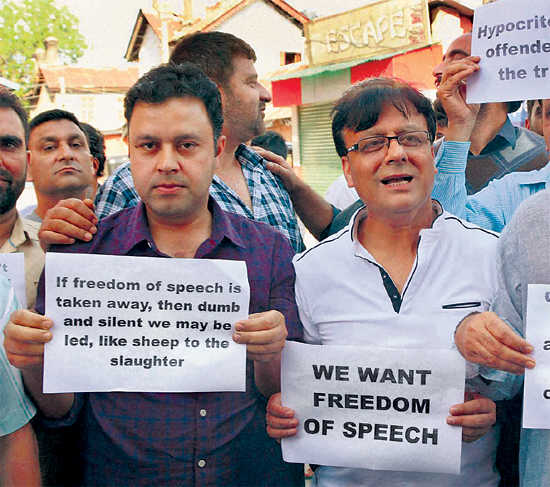

Journalists protest against the J-K government. PTI file

Journalists protest against the J-K government. PTI file

BRP BhaskarThe Tribune

Threats come dime a dozen these days. They make headlines, provoke social media outburst and then, in most cases, die down. But Kashmir has been a trouble-spot since long and appears to be at the beginning of a difficult phase. So BJP leader Chaudhary Lal Singh's warning to journalists in the valley, with an ominous allusion to the murder of Shujaat Bukhari, Editor of Rising Kashmir, merits attention in a wider context.

Lal Singh was one of two BJP ministers who attempted to block the filing of charge-sheet against the men the state police had nabbed in connection with the Kathua rape and murder case. Chief Minister Mehmooda Mufti got the BJP to replace the two ministers but the ministry did not survive long after that.

Journalism in Kashmir was never quite like what it was elsewhere in the country.

First, there was the Pakistani attempt to grab the state using a hastily mobilised tribal force. If the tribesmen had not tarried on the way to loot and rape, they could have taken Srinagar before the Maharaja signed the instrument of accession and India flew in troops. Then, there was the dismissal and arrest of Prime Minister Sheikh Abdullah to foil a suspected unilateral declaration of independence. For 22 years thereafter, India ensured a friendly government in the state by keeping him out of the election arena.

All this created a situation which cast on journalists the onerous responsibility of safeguarding the national interest. By and large, they gave no cause for offence. When they did, they were subtly reminded they were off-course. One journalist sent by a national daily, on returning home from an outing, found the place bare: the furniture and all his belongings were gone. He took the message and went back to Delhi.

National interest flew into my face when I landed there in 1973, exiled by my news agency. Chief Minister Syed Mir Qasim felt I had overlooked national interest in reporting protests in Ladakh, including a hartal in Leh, when he visited the region. A minister from Jammu felt I had overlooked his interest in reporting his son's arrest on a rape complaint filed by a foreigner. "You are the instrumentality through which I am being destroyed," he told me.

When the government moved to Jammu, I stayed back in Srinagar to experience the Kashmir winter. On a visit to Jammu, I called on the CM. He said he was sorry to hear of the burglary in my house. I told him there was no burglary until I left Srinagar.

The burglars came later, after I returned to Srinagar. They waited for me in the unlit house till I got back at night. I heard the sound of intruders moving in the house. I reckoned it was better to face them than risk being waylaid in a deserted street on a winter night. The bravado earned me head injuries which required 11 stitches. Their brief apparently was to wound, not kill.

Sheikh Abdullah once asked me: "Foreign correspondents come to meet me. I talk to them. They write a short report. What they write is what I said. Indian correspondents come to see me. I talk to them. They write long reports. What they write is not what I said. Why?" I told him: "I can think of two reasons. One, they don't understand you. Two, they understand you but they believe it is not in the country's interest. The problem is one of professional weakness and the solution is to strengthen professionalism."

A year and a half later, Abdullah was back, as CM. There was a relaxed atmosphere in Kashmir. Pakistan was unhappy. Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto called for a hartal in Kashmir the day the Sheikh came to the valley. The Chief Secretary flew to Srinagar and reminded journalists of their duty to uphold national interest.

Based on official accounts, we reported that Kashmiris had rejected Bhutto's call. But some of us did mention the closure of shops. A local Urdu newspaper provided its own account, with photographs of closed shops and deserted streets. When Pakistan TV got the paper three days later, it displayed it on the screen to convince its viewers that there was indeed a hartal.

Sheikh Abdullah criticised us for not telling the truth. Was Gandhiji's India to be built on falsehood, he asked.

Four months later came the Emergency, the censorship and the crawling. The valley was quiet and experiencing a level of freedom it had not known before. At the CM’s request, Mrs Gandhi transferred the power of censorship to the state government.

One morning, his censor told us not to report a speech Awami Action Committee Chairman Mirwaiz Mohammed Farooq was to deliver at the Jama Masjid that day. It was a legally untenable order as it was issued without knowing the speech content. The Mirwaiz criticised the Emergency but welcomed the PM's 20-point programme. The Emergency regime's main mouthpiece, All India Radio, picked up my report, omitted the first part and headlined the second. The censor ignored my defiance of his order.

When we sought his intervention in the case of a Kashmiri journalist whom Haryana CM Bansi Lal had detained, the Sheikh got the detenu shifted to a Kashmir jail and then got him released on parole.

Abdullah later inducted Mohammad Sayeed Malik, a journalist, as Director of Information, and he became the Chief Censor too. Thanks to his intimate knowledge of the problems of the reporters, the censorship phase passed uneventfully thereafter.

Militancy set in a few years after I left Kashmir. From my safe perch, I have been following with interest the work of Kashmiri journalists who are walking the razor's edge. English newspapers and websites have come up in Kashmir during this period, and I have admiration for the skill with which they negotiate the minefield, carrying the burden of the multiple interests they have to be watchful of.

When Shujaat Bukhari was killed, Mohammad Sayeed Malik wrote: "Over the past about three decades Kashmiris have developed sufficient sense and acquired sufficient 'experience' to make their own intelligent guess about both the hand behind the trigger and the motive of its dastardly act. In nine out of ten cases, their instinctive guess is right though they rarely risk sharing it publicly. Bukhari's case falls into that rare category where the precise determination of the killer as well as the motive can only be guessed vaguely, not determined with certainty."

Lal Singh's threat, if it is a serious one, adds one more to the interests journalists in Kashmir have to keep in mind while pursuing the profession in this perilous period. -- The Trubune. June 27, 2018.

No comments:

Post a Comment